Synaesthetic Syntax is a one-day symposium on Sunday 11th September as part of the 10th Expanded Animation section of the Ars Electronica Festival. The event explores the complex relationship between sensory perception and expanded animation. In focussing on the primacy of the senses, the symposium aims to ask questions about the seduction of technology and how to maintain a discourse of what is fundamental about being human. This year’s theme is touch, gesture and physical movement. For more details about the presentations and how to view them online, go to the website for Expanded Animation.

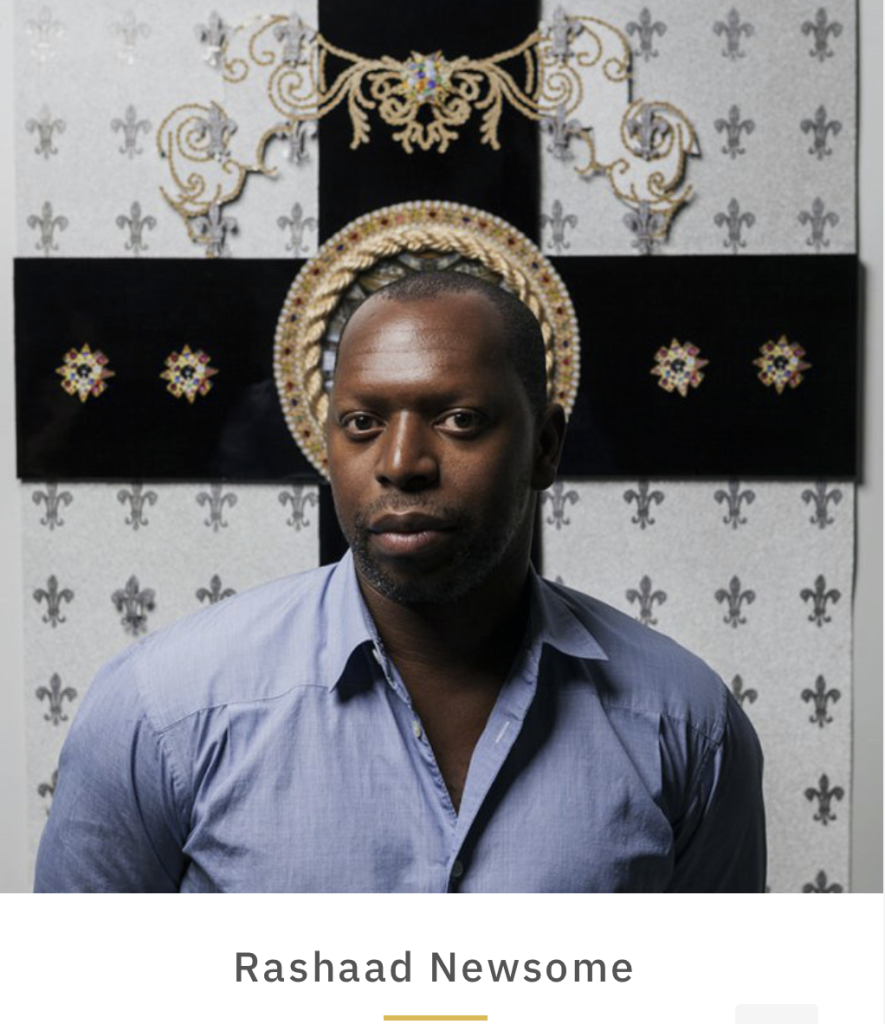

We are delighted to welcome our keynote speaker and winner of a Golden Nica at this years Prix Ars Electronica: Rashaad Newsome. He will be giving his keynote presentation at 14.00 (CET) on Friday 9th Sept.

To be human, to be in a body, is to move and to feel; to move as it feels and to feel itself moving.[1] However, bodies do not exist in isolation. Bodies collide with one another in social contexts. They have the power to affect others or to be affected themselves. Bodies are structured by culture, but they can also resist. Motion and sensation felt in the body leads to change.[2]

At the time of organising the symposium, a line of tanks, armoured vehicles and troops 40 miles long were approaching Kyev: literally illustrating change in motion through technology. How can animation respond to this? How might technologies of gesture, proprioception and motion be used to create animation that goes beyond formalism and is able to reflect upon the forces that seek to contain movements towards change?

The sensation of touch can be brutal and violent or tender and loving. Through ‘haptic visuality’[3], a sense of touch can be evoked in animation by triggering physical memories of smell, touch and taste that engages the viewer bodily to convey cultural experience rather than through a use of language. How can touch be used in animation to create community or share memories?

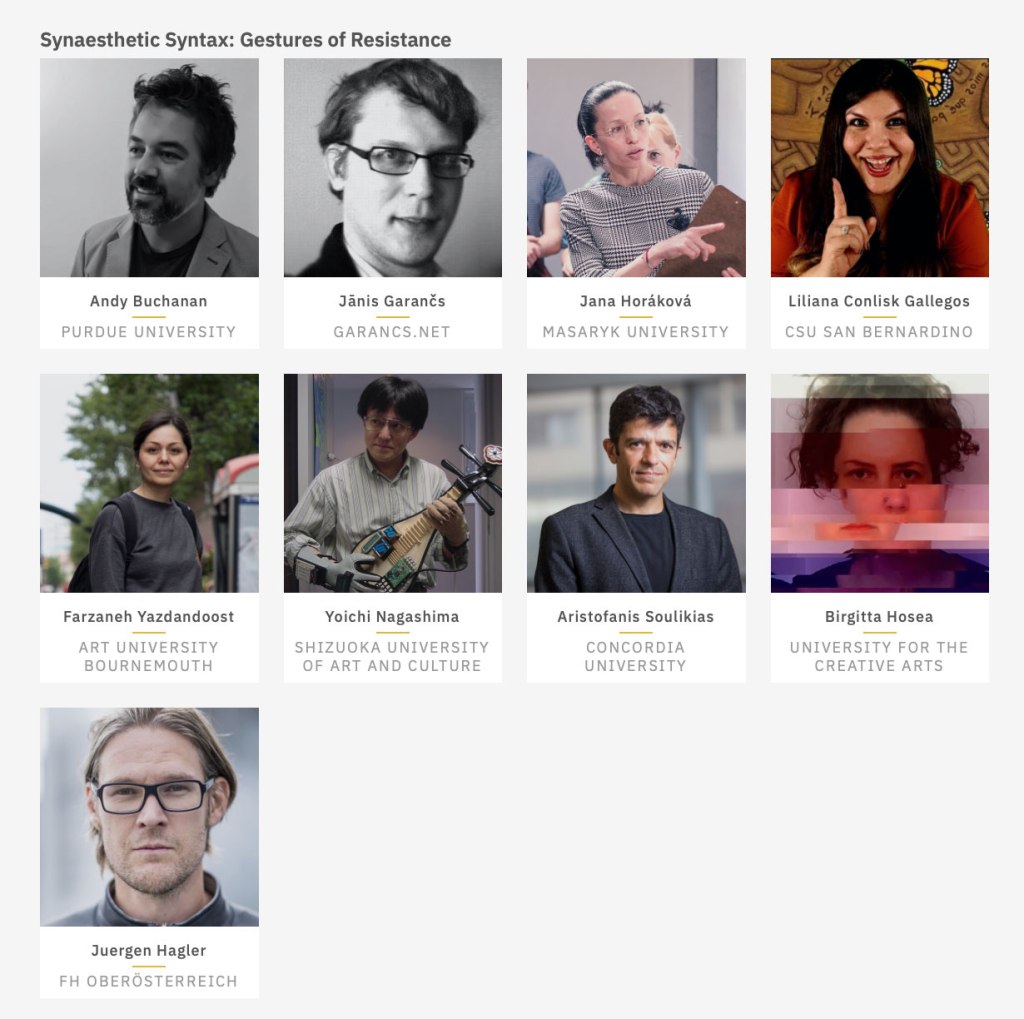

Presentations:

The presentations respond to the following questions:

- How to critically reflect on the tools and technologies of touch and movement used to create animation – motion capture, tablets and pens, sensors – and the data sets and libraries that they create?

- How might the capture of motion, gesture and proprioception be used to innovate and tell stories of new communities?

- What is the role of touch in conveying memory?

- How might touch and biofeedback data be used in new ways to create animation?

[1] Paraphrase from p1. Brian Massumi, Parables for the Virtual: Movement, Affect, Sensation (2002, Duke University Press)

[2] Cf. Massumi, op. cit.

[3] Laura U Marks, The Skin of the Film: Intercultural Cinema, Embodiment and the Senses (2000, Duke University Press)